I admit, that this next fact, may indeed come as quite a surprise to many of you; but way back in the nineties, it was discovered that the brain is chalk full of these minuscule crystals,

well, one in specific actually…

These brain-swimming ‘crystals’, are called magnetite;

a mineral that is naturally MAGNETIC, & composed of

iron-oxide.

THE MINERAL MAGNETITE: Chemical Formula: Fe3O4, Iron Oxide. Class: Oxides and Hydroxides.

So at this very moment, as you now read this, millions of these tiny, little crystals, lie buried deep within your brain.

Researchers have now uncovered, in the years since their initial discovery of the mineral’s general presence in our body, that clumps of magnetite can be found in EVERY cell of the entire brain.

For years, prior to this revelation, scientists had already understood that the mineral existed in every other animal , yet, assumed at the time, not in humans.

Magnetite in and of itself, although seemingly extraordinary in its ability to exist within our brain, is not some super powered sci-fi movie material. In fact, it is a quite common iron oxide (Fe3O4) mineral; typically found in igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks, naturally.

Today this mineral, which stands abundantly scattered throughout our brains, is actually the most commonly mined iron ore on the planet, as well as the one with the greatest iron content, at around (72.4%).

In modern times, it is mined as iron ore, a metal, which we use in a wide variety of everyday objects, and does not really seem all too special. Yet, out of all the naturally-occurring minerals found on planet Earth; it is perhaps, the single most magnetic.

Lodestone, the name given naturally-magnetized pieces of magnetite, will draw in small bits of iron. Now, in palaeolithic times, this naturally magnetic pull was the way in which ancient peoples were initially exposed to the property of magnetism(basic as it was).

Now,

although not yet fully understood;

for the intended purposes of this piece, we must now return to our brain’s relationship, with the mineral.

Powerful Demonstrations of How Magnets Can Affect Your Brain. Magnetic fields can improve your memory and even control your behavior and sense of morality. … The magnets stimulate electrical responses in the brain. Transcranial direct current stimulation is just what it sounds, applying the current directly to the brain.

- The homing pigeon can return to its home using its ability to sense the Earth’s magnetic field and other cues to orient itself.

- Fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster needs cryptochrome to respond to magnetic fields.

- Several mammals, including the big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus) can use magnetic fields for orientation.

Maverick scientist thinks he has discovered a magnetic sixth sense in humans

Birds do it. Bees do it. But the human subject, standing here in a hoodie—can he do it? Joe Kirschvink is determined to find out. For decades, he has shown how critters across the animal kingdom navigate using magnetoreception, or a sense of Earth’s magnetic field. Now, the geophysicist at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena is testing humans to see if they too have this subconscious sixth sense. Kirschvink is pretty sure they do. But he has to prove it.

They are two floors underground at Caltech, in a clean room with magnetically shielded walls. In a corner, a liquid helium pump throbs and hisses, cooling a superconducting instrument that Kirschvink has used to measure tiny magnetic fields in everything from bird beaks to martian meteorites. On a lab bench lie knives—made of ceramic and soaked in acid to eliminate magnetic contamination—with which he has sliced up human brains in search of magnetic particles. Matsuda looks a little nervous, but he will not be going under the knife. With a syringe, a technician injects electrolyte gel onto Matsuda’s scalp through a skullcap studded with electrodes. He is about to be exposed to custom magnetic fields generated by an array of electrical coils, while an electroencephalogram (EEG) machine records his brain waves.

For much of the 20th century, magnetoreception research seemed as unsavory as the study of dowsing or telepathy. Yet it is now an accepted fact that many animals sense the always-on, barely there magnetic field of Earth. Birds, fish, and other migratory animals dominate the list; it makes sense for them to have a built-in compass for their globetrotting journeys. In recent years, researchers have found that less speedy creatures—lobsters, worms, snails, frogs, newts—possess the sense. Mammals, too, seem to respond to Earth’s field: In experiments, wood mice and mole rats use magnetic field lines in siting their nests; cattle and deer orient their bodies along them when grazing; and dogs point themselves north or south when they urinate or defecate.

Playing the field

Earth’s magnetic field, generated by its liquid outer core, is similar to that of a giant off-axis bar magnet. Its strength ranges from 25 microtesla (μT) near the equator to 60 μT at the poles. That is weak: An MRI’s field is more than 100,000 times stronger.

The mounting scientific evidence for magnetoreception has largely been behavioral, based on patterns of movement, for example, or on tests showing that disrupting or changing magnetic fields can alter animals’ habits. Scientists know that animals can sense the fields, but they do not know how at the cellular and neural level. “The frontier is in the biology—how the brain actually uses this information,” says David Dickman, a neurobiologist at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, who in a 2012 Science paper showed that specific neurons in the inner ears of pigeons are somehow involved, firing in response to the direction, polarity, and intensity of magnetic fields.

Finding the magnetoreceptors responsible for triggering these neurons has been like looking for a magnetic needle in a haystack. There’s no obvious sense organ to dissect; magnetic fields sweep invisibly through the entire body, all the time. “The receptors could be in your left toe,” Kirschvink says.

Scientists have come up with two rival ideas about what they might be. One is that magnetic fields trigger quantum chemical reactions in proteins called cryptochromes. Cryptochromes have been found in the retina, but no one has determined how they might control neural pathways. The other theory, which Kirschvink favors, proposes that miniature compass needles sit within receptor cells, either near the trigeminal nerve behind animals’ noses or in the inner ear. The needles, presumed to be made up of a strongly magnetic iron mineral called magnetite, would somehow open or close neural pathways.

The same candidate magnetoreceptors are found in humans. So do we have a magnetic sense as well? “Perhaps we lost it with our civilization,” says Michael Winklhofer, a biophysicist at the University of Oldenburg in Germany. Or, as Kirschvink thinks, perhaps we retain a vestige of it, like the wings of an ostrich.

Kirschvink specializes in measuring remanent magnetic fields in rock, which can indicate the latitude at which the rock formed, millions or billions of years ago, and can trace its tectonic wanderings. The technique has led him to powerful, influential ideas. In 1992, he marshaled evidence that glaciers nearly covered the globe more than 650 million years ago, and suggested that their subsequent retreat from “Snowball Earth” (a term he coined) triggered an evolutionary sweepstakes that would become the Cambrian explosion 540 million years ago. In 1997, he worked out a provocative explanation for the abnormally speedy drift of continental plates about the same time as the Cambrian explosion: Earth’s rotational axis had tipped over by as much as 90°, Kirschvink proposed. The climatic havoc from this geologically sudden event also would have spurred the biological innovations seen in the Cambrian. And he was prominent among a group of scientists who in the 1990s and 2000s argued that magnetic crystals in a famous martian meteorite, Allan Hills 84001, were fossilized signs of life on the Red Planet. Although the significance of Allan Hills 84001 remains controversial, the idea that life leaves behind magnetofossils is an active area of research on Earth.

“He’s not afraid to go out on a limb,” says Kenneth Lohmann, a neurobiologist who studies magnetoreception in lobsters and sea turtles at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. “He’s been right about some things and not right about other things.”

It’s part of our evolutionary history. Magnetoreception may be the primal sense.

In support of his hypotheses, Kirschvink has gathered rocks from all over the world: South Africa, China, Morocco, and Australia. But looking for magnets in animals—and humans—in his windowless subbasement lab has remained an abiding obsession. Just ask his first-born son, who arrived in 1984, as Kirschvink and his wife—Atsuko Kobayashi, a Japanese structural biologist—published the discovery of magnetite in the sinus tissue of yellowfin tuna. At Kirschvink’s suggestion, they named him Jiseki: magnet stone, or magnetite.

Kirschvink, 62, could never decide between geology and biology. He remembers the day in 1972 when, as an undergraduate at Caltech, he realized that the two were intertwined. A professor held the tongue plate of a chiton, a type of mollusk, and dragged it around with a bar magnet. Its teeth were capped with magnetite. “That blew me away,” recalls Kirschvink, who still keeps the tongue plate on his desk. “Magnetite is typically something that geologists expect in igneous rocks. To find it in an animal is a biochemical anomaly.”

For many years, scientists thought chitons had evolved a way to synthesize magnetite simply because the hard mineral makes for a good, strong tooth. But in 1975, Richard Blakemore at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts suggested that in certain bacteria, magnetite is a magnetic sensor. Studying bacteria from Cape Cod marsh muds, Blakemore found that when he moved a small magnet around his glass slides, the bacteria would rush toward the magnet. Looking closer, he found that the microbes harbored chains of magnetite crystals that forced the cells to align with the lines of Earth’s own magnetic field, which in Massachusetts dip down into the ground at 70°, toward the North Pole. Many bacteria search randomly for the right balance of oxygen and nutrients, utilizing a motion called “tumble and run.” But as swimming compass needles, Blakemore’s bacteria knew up-mud from down-mud. They could surf this gradient more efficiently and would swim downward along it whenever the mud was disturbed. These bacterial magnetoreceptors are still the only ones scientists have definitively located and studied. To Kirschvink, their presence indicates that magnetoreception is ancient, perhaps predating Earth’s first eukaryotic cells, which are thought to have evolved nearly 2 billion years ago after a host cell captured free-living bacteria that became the cell’s energy-producing mitochondria. “I’m suggesting that the original mitochondria were magnetic bacteria,” Kirschvink says, which could mean that all eukaryotes have a potential magnetic sense.

Reading about Blakemore’s work, Kirschvink wondered which way magnetic bacteria swim in the Southern Hemisphere: northward like the Massachusetts microbes, or southward toward their own pole, or in some other direction? He flew to Australia to search stream beds for Blakemore’s antipodal counterparts. They were most abundant in a sewage treatment pond near Canberra. “I just went with a magnet and hand lens,” he says. “They’re all over the place.” Sure enough, they swam down toward the South Pole. They had evolved south-seeking magnetite chains.

By then, Kirschvink was a postdoc at Princeton University, working with biologist James Gould. He had also graduated up the food chain of animals. In 1978, he and Gould found magnetite in the abdomen of honey bees. Then, in 1979, in the heads of pigeons. Unbeknownst to Kirschvink, across the Atlantic Ocean a young, charismatic University of Manchester, U.K., biologist named Robin Baker was setting his sights on the magnetic capabilities of larger, more sophisticated animals: British students. In a series of experiments, he gathered blindfolded students from a “home” point onto a Sherpa minibus, took them on a tortuous route into the countryside, and asked them the compass direction of home. In Science in 1980, Baker reported something uncanny: The students could almost always point in the quadrant of home. When they wore a bar magnet in the elastic of their blindfolds, that pointing skill was thwarted, whereas controls who wore a brass bar still had what appeared to be a magnetic sense.

In later variations, Baker claimed to find a human compass sense in “walkabout” experiments, in which subjects pointed home after being led on a twisty route; and “chair” experiments, in which they were asked for cardinal directions after being spun around. Baker performed some of his experiments for live television, and he announced some of his results prior to peer review in books and popular science magazines—a flair for the dramatic that rubbed other academics the wrong way.

In an email, Baker says there was a “base hostility” among his U.S. counterparts. Kirschvink and Gould were among the skeptics. In 1981, they invited Baker to Princeton for a chance to perform the experiments, one whistle stop on a reproducibility tour of several U.S. campuses in the Northeast. At Princeton and elsewhere, the replication efforts failed. After Baker claimed in a 1983 Nature paper that human sinus bones were magnetic, Kirschvink showed that the results were due to contamination. In 1985, Kirschvink failed to replicate a version of the chair experiment.

Although the Manchester experiments cast a pall over human magnetoreception, Kirschvink quietly took up Baker’s mantle, pursuing human experiments on the side for 30 years. He never gave up running students through a gauntlet of magnetic coils and experimental protocols. “The irritating thing was, [our] experiments were not negative,” he says. “But from day to day, we couldn’t reproduce them.”

Now, with a $900,000 grant from the Human Frontier Science Program, Kirschvink; Shinsuke Shimojo, a Caltech psychophysicist and EEG expert; and Ayumu Matani, a neuroengineer at the University of Tokyo, are making their best effort ever to test Baker’s claims.

Baker finds it ironic that his onetime antagonist is now leading the charge for human magnetoreception. “Joe is probably in a better position to do this than most,” he writes. As for whether he thinks his results still indicate something real, Baker says there is “not a shadow of doubt in my mind: Humans can detect and use the Earth’s magnetic field.”

Center of attraction

Researchers are testing humans for a subconscious magnetic sense by putting them in a dark metal box and applying magnetic fields.

Next door to Kirschvink’s magnetics lab is the room where he tests his human subjects. In it is a box of thin aluminum siding, known as a Faraday cage, just big enough to hold the test subject. Its role is to screen out electromagnetic noise—from computers, elevators, even radio broadcasts—that might confound the experiment. “The Faraday cage is key,” Kirschvink says. “It wasn’t until the last few years, after we put the damned Faraday shield in, that we went, ‘Wait a minute.’”

Kirschvink added it after an experiment led by one of Winklhofer’s Oldenburg colleagues, Henrik Mouritsen, showed that electromagnetic noise prevents European robins from orienting magnetically. The stray fields would probably affect any human compass, Kirschvink says, and the noise is most disruptive in a band that overlaps with AM radio broadcasts. That could explain why Baker’s experiments succeeded in Manchester, which at the time did not have strong AM radio stations. The U.S. Northeast, however, did, which could explain why scientists there couldn’t replicate the findings.

In the current setup, the Faraday cage is lined with squares of wire coils, called Merritt coils. Electricity pulsed through the coils induces a uniform magnetic field running through the center of the box. Because the coils are arranged in three perpendicular directions, the experimenters can control the orientation of the field. A fluxgate magnetometer to check field strength dangles above a wooden chair that has had all of its iron-containing parts replaced with nonmagnetic brass screws and aluminum brackets.

Kirschvink, Shimojo, and Matani’s idea is to apply a rotating magnetic field, similar in strength to Earth’s, and to check EEG recordings for a response in the brain. Finding one would not reveal the magneto-receptors themselves, but it would prove that such a sense exists, with no need to interpret often-ambiguous human behavior. “It’s a really fantastic idea,” Winklhofer says. “I’m wondering why nobody has tried it before.”

The experiments began at the end of 2014. Kirschvink was human subject No. 1. No. 19 is Matsuda, on loan from Matani’s lab, which is replicating the experiment in Tokyo with a similar setup. Matsuda signs a consent form and is led into the box by the technician, who carries the EEG wires like the train of a wedding veil. “Are we ready to start?” the technician asks, after plugging in the electrodes. Matsuda nods grimly. “All right, I’ll shut the box.” He lowers the flap of aluminum, turns off the lights, and shuts the door. Piped into the box is Kirschvink’s nasal, raspy voice. “Don’t fall asleep,” he says.

Matsuda will sit in the box for an hour in total blackness while an automated program runs through eight different tests. In half of them, a magnetic field roughly as strong as Earth’s rotates slowly around the subject’s head. In the others, the Merritt coils are set to cancel out the induced field so that only Earth’s natural magnetism is at work. These tests are randomized so that neither experimenter nor subject knows which is which.

Every few years, the Royal Institute of Navigation (RIN) in the United Kingdom holds a conference that draws just about every researcher in the field of animal navigation. Conferences from years past have dwelt on navigation by the sun, moon, or stars—or by sound and smell. But at this year’s meeting, in April at Royal Holloway, University of London, magnetoreception dominated the agenda. Evidence was presented for magnetoreception in cockroaches and poison frogs. Peter Hore, a physical chemist at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, presented work showing how the quantum behavior of the cryptochrome system could make it more precise than laboratory experiments had suggested. Can Xie, a biophysicist from Peking University, pressed his controversial claim that, in the retina of fruit flies, he had found a complex of magnetic iron structures, surrounded by cryptochrome proteins, that was the long-sought magnetoreceptor.

Then, in the last talk of the first day, Kirschvink took the podium to deliver his potentially groundbreaking news. It was a small sample—just two dozen human subjects—but his basement apparatus had yielded a consistent, repeatable effect. When the magnetic field was rotated counterclockwise—the equivalent of the subject looking to the right—there was sharp drop in α waves. The suppression of α waves, in the EEG world, is associated with brain processing: A set of neurons were firing in response to the magnetic field, the only changing variable. The neural response was delayed by a few hundred milliseconds, and Kirschvink says the lag suggests an active brain response. A magnetic field can induce electric currents in the brain that could mimic an EEG signal—but they would show up immediately.

Kirschvink also found a signal when the applied field yawed into the floor, as if the subject had looked up. He does not understand why the α wave signal occurred with up-down and counterclockwise changes, but not the opposite, although he takes it as a sign of the polarity of the human magnetic compass. “My talk went *really* well,” he wrote jubilantly in an email afterwards. “Nailed it. Humans have functioning magnetoreceptors.”

Others at the talk had a guarded response: amazing, if true. “It’s the kind of thing that’s hard to evaluate from a 12-minute talk,” Lohmann says. “The devil’s always in the details.” Hore says: “Joe’s a very smart man and a very careful experimenter. He wouldn’t have talked about this at the RIN if he wasn’t pretty convinced he was right. And you can’t say that about every scientist in this area.”

Two months later, in June, Kirschvink is in Japan, crunching data and hammering out experimental differences with Matani’s group. “Alice in Wonderland, down the rabbit hole, that’s what it feels like,” he says. Matani is using a similarly shielded setup, except his cage and coils are smaller—just big enough to encompass the heads of subjects, who must lie on their backs. Yet this team, too, is starting to see repeatable EEG effects. “It’s absolutely reproducible, even in Tokyo,” Kirschvink says. “The doors are opening.”

Kirschvink’s lifelong quest seems to be on the cusp of resolution, but it also feels like a beginning. A colleague in New Zealand says he is ready to replicate the experiment in the Southern Hemisphere, and Kirschvink wants money for a traveling Faraday cage that he could take to the magnetic equator. There are papers to write, and new subjects to recruit. Just as Baker’s results ricocheted through the research community for years, Kirschvink knows that the path toward getting his idea accepted is long, and uphill.

But he relishes the thought of showing, once and for all, that there is something that connects the iPhone in his pocket—the electromagnetic laws that drive devices and define modernity—to something deep inside him, and the tree of life. “It’s part of our evolutionary history. Magnetoreception may be the primal sense.”

wisdom,

wisdom,

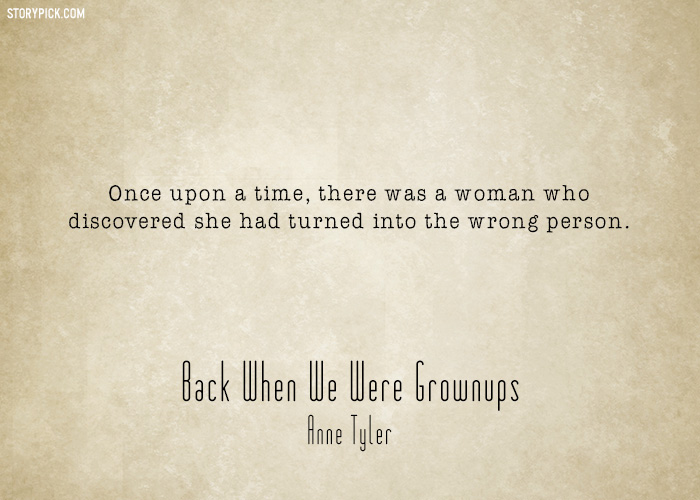

—Anne Tyler, Back When We Were Grownups (2001)

—Anne Tyler, Back When We Were Grownups (2001)

—who, after the war the Second World War, had come to America the land of opportunities from France under the sponsorship of his uncle—a journalist, fluent in five languages—who himself had come to America from Europe Poland it seems, though this was not clearly established sometime during the war after a series of rather gruesome adventures, and who, at the end of the war, wrote to the father his cousin by marriage of the young man whom he considered as a nephew, curious to know if he the father and his family had survived the German occupation, and indeed was deeply saddened to learn, in a letter from the young man—a long and touching letter written in English, not by the young man, however, who did not know a damn word of English, but by a good friend of his who had studied English in school—that his parents both his father and mother and his two sisters one older and the other younger than he had been deported they were Jewish to a German concentration camp Auschwitz probably and never returned, no doubt having been exterminated deliberately X * X * X * X, and that, therefore, the young man who was now an orphan, a displaced person, who, during the war, had managed to escape deportation by working very hard on a farm in Southern France, would be happy and grateful to be given the opportunity to come to America that great country he had heard so much about and yet knew so little about to start a new life, possibly go to school, learn a trade, and become a good, loyal citizen.”

—who, after the war the Second World War, had come to America the land of opportunities from France under the sponsorship of his uncle—a journalist, fluent in five languages—who himself had come to America from Europe Poland it seems, though this was not clearly established sometime during the war after a series of rather gruesome adventures, and who, at the end of the war, wrote to the father his cousin by marriage of the young man whom he considered as a nephew, curious to know if he the father and his family had survived the German occupation, and indeed was deeply saddened to learn, in a letter from the young man—a long and touching letter written in English, not by the young man, however, who did not know a damn word of English, but by a good friend of his who had studied English in school—that his parents both his father and mother and his two sisters one older and the other younger than he had been deported they were Jewish to a German concentration camp Auschwitz probably and never returned, no doubt having been exterminated deliberately X * X * X * X, and that, therefore, the young man who was now an orphan, a displaced person, who, during the war, had managed to escape deportation by working very hard on a farm in Southern France, would be happy and grateful to be given the opportunity to come to America that great country he had heard so much about and yet knew so little about to start a new life, possibly go to school, learn a trade, and become a good, loyal citizen.”